THE WHITE BUFFALO WOMAN

The Sioux are a warrior tribe, and one of their proverbs says, “Woman shall not walk before man.” Yet White Buffalo Woman is the dominant figure of their most important legend. The medicine man Crow Dog explains, “This holy woman brought the sacred buffalo calf pipe to the Sioux. There could be no Indians without it. Before she came, people didn’t know how to live. They knew nothing. The Buffalo Woman put her sacred mind into their minds.” At the ritual of the sun dance, one woman, usually a mature and universally respected member of the tribe, is given the honor of representing Buffalo Woman.

Though she first appeared to the Sioux in human form, White Buffalo Woman was also a buffalo—the Indians’ brother, who gave its flesh so that the people might live. Albino buffalo were sacred to all Plains tribes; a white buffalo hide was a sacred talisman, a possession beyond price.

One summer so long ago that nobody knows how long, the Oceti Shakowin, the seven sacred council fires of the Lakota Oyate, the nation, came together and camped. The sun shone all the time, but there was no game and the people were starving. Every day they sent scouts to look for game, but the scouts found nothing.

Among the bands assembled were the Itazipcho, the Without-Bows, who had their own camp circle under their chief, Standing Hollow Horn. Early one morning, the chief sent two of his young men to hunt for game. They went on foot, because at that time the Sioux didn’t yet have horses. They searched everywhere but could find nothing. Seeing a high hill, they decided to climb it in order to look over the whole country. Halfway up, they saw something coming toward them from far off, but the figure was floating instead of walking. From this they knew that the person was wakan, holy.

At first they could make out only a small moving speck and had to squint to see that it was a human form. But as it came nearer, they realized that it was a beautiful young woman, more beautiful than any they had ever seen, with two round, red dots of face paint on her cheeks. She wore a wonderful white buckskin outfit, tanned until it shone a long way in the sun. It was embroidered with sacred and marvelous designs of porcupine quill, in radiant colors no ordinary woman could have made. This wakan stranger was Ptesan-Wi, White Buffalo Woman. In her hands, she carried a large bundle and a fan of sage leaves. She wore her blue-black hair loose except for a strand at the left side, which was tied up with buffalo fur. Her eyes shone dark and sparkling, with great power in them.

The two young men looked at her open-mouthed. One was overawed, but the other desired her body and stretched his hand out to touch her. This woman was lila wakan, very sacred, and could not be treated with disrespect. Lightning instantly struck the brash young man and burned him up, so that only a small heap of blackened bones was left. Or some say that he was suddenly covered by a cloud, and within it, he was eaten up by snakes that left only his skeleton, just as a man can be eaten up by lust.

To the other scout who had behaved rightly, the White Buffalo Woman said: “Good things I am bringing, something holy to your nation. A message I carry for your people from the buffalo nation. Go back to the camp and tell the people to prepare for my arrival. Tell your chief to put up a medicine lodge with twenty-four poles. Let it be made holy for my coming.”

This young hunter returned to the camp. He told the chief, he told the people, what the sacred woman had commanded. The chief told the eyapaha, the crier, and the crier went through the camp circle calling: “Someone sacred is coming. A holy woman approaches. Make all things ready for her.” So the people put up the big medicine tipi and waited. After four days they saw the White Buffalo Woman approaching, carrying her bundle before her. Her wonderful white buckskin dress shone from afar. The chief, Standing Hollow Horn, invited her to enter the medicine lodge. She went in and circled the interior sunwise. The chief addressed her respectfully, saying: “Sister, we are glad you have come to instruct us.”

She told him what she wanted done. In the center of the tipi, they were to put up an owanka wakan, a sacred altar, made of red earth, with a buffalo skull and a three-stick rack for a holy thing she was bringing. They did what she directed, and she traced a design with her finger on the smoothed earth of the altar. She showed them how to do all this, then circled the lodge again sunwise. Halting before the chief, she now opened the bundle. The holy thing it contained was the chanunpa, the sacred pipe. She held it out to the people and let them look at it. She was grasping the stem with her right hand and the bowl with her left, and thus the pipe has been held ever since.

Again the chief spoke, saying: “Sister, we are glad. We have had no meat for some time. All we can give you is water.” They dipped some wacanga, sweet grass, into a skin bag of water and gave it to her, and to this day the people dip sweet grass or an eagle wing in water and sprinkle it on a person to be purified.

The White Buffalo Woman showed the people how to use the pipe. She filled it with chan-shasha, red willow-bark tobacco. She walked around the lodge four times after the manner of Anpetu-Wi, the great sun. This represented the circle without end, the sacred hoop, the road of life. The woman placed a dry buffalo chip on the fire and lit the pipe with it. This was peta-owihankeshni, the fire without end, the flame to be passed on from generation to generation. She told them that the smoke rising from the bowl was Tunkashila’s breath, the living breath of the great Grandfather Mystery.

The White Buffalo Woman showed the people the right way to pray, the right words, and the right gestures. She taught them how to sing the pipe-filling song and how to lift the pipe up to the sky, toward Grandfather, and down toward Grandmother Earth, to Unci, and then to the four directions of the universe.

“With this holy pipe,” she said, “you will walk like a living prayer. With your feet resting upon the earth and the pipestem reaching into the sky, your body forms a living bridge between the Sacred Beneath and the Sacred Above. Wakan Tanka smiles upon us because now we are as one: earth, sky, all living things, the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged ones, the trees, the grasses. Together with the people, they are all related, one family. The pipe holds them all together.

“Look at this bowl,” said the White Buffalo Woman. “Its stone represents the buffalo, but also the flesh and blood of the red man. The buffalo represents the universe and the four directions, because he stands on four legs, for the four ages of creation. The buffalo was put in the west by Wakan Tanka at the making of the world, to hold back the waters. Every year he loses one hair, and in every one of the four ages, he loses a leg. The sacred hoop will end when all the hair and legs of the great buffalo are gone, and the water comes back to cover the Earth.

The wooden stem of this chanunpa stands for all that grows on the earth. Twelve feathers hanging from where the stem—the backbone—joins the bowl—the skull—are from Wanblee Galeshka, the spotted eagle, the very sacred bird who is the Great Spirit’s messenger and the wisest of all flying ones. You are joined to all things of the universe, for they all cry out to Tunkashila. Look at the bowl: engraved in it are seven circles of various sizes. They stand for the seven sacred ceremonies you will practice with this pipe, and for the Ocheti Shakowin, the seven sacred campfires of our Lakota nation.”

The White Buffalo Woman then spoke to the women, telling them that it was the work of their hands and the fruit of their bodies which kept the people alive. “You are from mother earth,” she told them. “What you are doing is as great as what the warriors do.”

And therefore, the sacred pipe is also something that binds men and women together in a circle of love. It is the one holy object in the making of which both men and women have a hand. The men carve the bowl and make the stem; the women decorate it with bands of colored porcupine quills. When a man takes a wife, they both hold the pipe at the same time, and red trade cloth is wound around their hands, thus tying them together for life.

The White Buffalo Woman had many things for her Lakota sisters in her sacred womb bag—corn, wasna (pemmican), wild turnip. She taught them how to make the hearth fire. She filled a buffalo paunch with cold water and dropped a red-hot stone into it. “This way you shall cook the corn and the meat,” she told them.

The White Buffalo Woman also talked to the children because they have an understanding beyond their years. She told them that what their fathers and mothers did was for them, that their parents could remember being little once, and that they, the children, would grow up to have little ones of their own. She told them: “You are the coming generation, that’s why you are the most important and precious ones. Someday you will hold this pipe and smoke it. Someday you will pray with it.”

She spoke once more to all the people: “The pipe is alive; it is a red being showing you a red life and a red road. And this is the first ceremony for which you will use the pipe. You will use it to keep the soul of a dead person, because through it you can talk to Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery Spirit. The day a human dies is always a sacred day. The day when the soul is released to the Great Spirit is another. Four women will become sacred on such a day. They will be the ones to cut the sacred tree—the can-wakan—for the sun dance.”

She told the Lakota that they were the purest among the tribes, and for that reason, Tunkashila had bestowed upon them the holy chanunpa. They had been chosen to take care of it for all the Indian people on this turtle continent.

She spoke one last time to Standing Hollow Horn, the chief, saying, “Remember: this pipe is very sacred. Respect it, and it will take you to the end of the road. The four ages of creation are in me; I am the four ages. I will come to see you in every generation cycle. I shall come back to you.”

The sacred woman then took leave of the people, saying: “Toksha ake wacinyanktin ktelo—I shall see you again.”

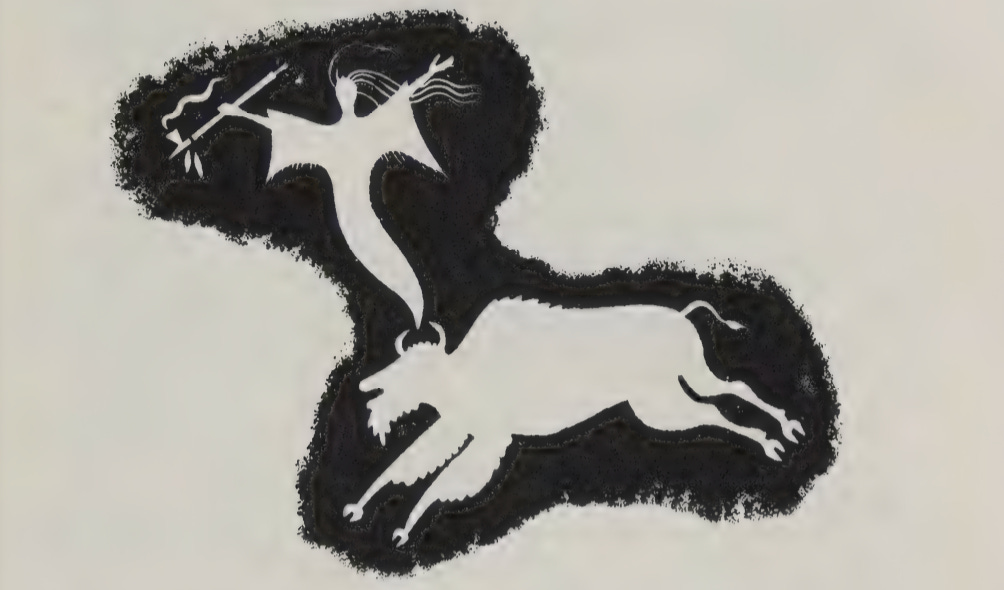

The people saw her walking off in the same direction from which she had come, outlined against the red ball of the setting sun. As she went, she stopped and rolled over four times. The first time, she turned into a black buffalo; the second into a brown one; the third into a red one; and finally, the fourth time she rolled over, she turned into a white female buffalo calf. A white buffalo is the most sacred living thing you could ever encounter.

The White Buffalo Woman disappeared over the horizon. Sometime she might come back. As soon as she had vanished, buffalo in great herds appeared, allowing themselves to be killed so that the people might survive. And from that day on, our relations, the buffalo, furnished the people with everything they needed—meat for their food, skins for their clothes and tipis, bones for their many tools.

—Told by Lame Deer at Winner, Rosebud Indian Reservation, South Dakota, 1967.

Two very old tribal pipes are kept by the Looking Horse family at Eagle Butte in South Dakota. One of them, made from a buffalo calf’s leg bone, too fragile and brittle with age to be used for smoking, is said to be the sacred pipe which the Buffalo Maiden brought to the people. “I know,” said Lame Deer. “I prayed with it once, long ago.”

The turtle continent is North America, which many Indian tribes regard as an island sitting on the back of a turtle.

John Fire Lame Deer was a famous Sioux “holy man,” grandson of the first Chief Lame Deer, a great warrior who fought Custer and died during a skirmish with General Miles. Lame Deer’s son, Archie, is carrying on his work as a medicine man and director of the sun dance.

LA MUJER BÚFALO BLANCO [BRULE SIOUX]

Los Sioux son una tribu guerrera, y uno de sus proverbios dice: “La mujer no debe caminar delante del hombre”. Sin embargo, la Mujer Búfalo Blanco es la figura dominante de su leyenda más importante. El hombre medicina Crow Dog explica: “Esta mujer sagrada trajo la pipa sagrada del ternero de búfalo a los Sioux. No podría haber indios sin ella. Antes de que ella llegara, la gente no sabía cómo vivir. No sabían nada. La Mujer Búfalo puso su mente sagrada en sus mentes”. En el ritual del baile del sol, se otorga el honor a una mujer, generalmente una miembro madura y universalmente respetada de la tribu, de representar a la Mujer Búfalo.

Aunque apareció por primera vez a los Sioux en forma humana, la Mujer Búfalo Blanco también era un búfalo —el hermano de los indios, que dio su carne para que la gente pudiera vivir. Los búfalos albinos eran sagrados para todas las tribus de las llanuras; una piel de búfalo blanco era un talismán sagrado, una posesión invaluable.

Un verano hace tanto tiempo que nadie sabe cuánto, el Oceti Shakowin, las siete hogueras sagradas del consejo de los Lakota Oyate, la nación, se reunieron y acamparon. El sol brillaba todo el tiempo, pero no había caza y la gente se estaba muriendo de hambre. Todos los días enviaban exploradores en busca de caza, pero los exploradores no encontraban nada.

Entre las bandas reunidas estaban los Itazipcho, los Sin Arcos, que tenían su propio círculo de campamento bajo su jefe, Cuerno Hueco Erguido. Una mañana temprano, el jefe envió a dos de sus jóvenes a cazar. Fueron a pie, porque en ese tiempo los Sioux aún no tenían caballos. Buscaron por todas partes pero no encontraron nada. Al ver una colina alta, decidieron subirla para observar todo el país. A mitad de camino, vieron algo que venía hacia ellos desde lejos, pero la figura flotaba en lugar de caminar. De esto supieron que la persona era wakan, sagrada.

Al principio solo pudieron distinguir un pequeño punto en movimiento y tuvieron que entrecerrar los ojos para ver que era una forma humana. Pero a medida que se acercaba, se dieron cuenta de que era una hermosa joven, más bella que cualquier otra que hubieran visto jamás, con dos puntos rojos redondos de pintura en las mejillas. Llevaba un maravilloso atuendo de piel de ciervo blanca, curtida hasta brillar a lo lejos en el sol. Estaba bordado con diseños sagrados y maravillosos de púas de puercoespín, en colores radiantes que ninguna mujer ordinaria podría haber hecho. Esta extraña wakan era Ptesan-Wi, la Mujer Búfalo Blanco. En sus manos llevaba un gran paquete y un abanico de hojas de salvia. Llevaba su cabello azul-negro suelto excepto por un mechón en el lado izquierdo, que estaba atado con piel de búfalo. Sus ojos brillaban oscuros y chispeantes, con gran poder en ellos.

Los dos jóvenes la miraron con la boca abierta. Uno estaba impresionado, pero el otro deseaba su cuerpo y extendió la mano para tocarla. Esta mujer era lila wakan, muy sagrada, y no podía ser tratada con irrespeto. Un rayo golpeó instantáneamente al joven imprudente y lo quemó, de modo que solo quedó un pequeño montón de huesos ennegrecidos. O algunos dicen que de repente fue cubierto por una nube, y dentro de ella fue devorado por serpientes que solo dejaron su esqueleto, tal como un hombre puede ser devorado por la lujuria.

Al otro explorador que se había comportado correctamente, la Mujer Búfalo Blanco le dijo: “Traigo cosas buenas, algo sagrado para tu nación. Llevo un mensaje para tu pueblo de la nación del búfalo. Vuelve al campamento y dile a la gente que se prepare para mi llegada. Dile a tu jefe que levante una cabaña de medicina con veinticuatro postes. Déjala ser santificada para mi llegada.”

Este joven cazador regresó al campamento. Le contó al jefe, le contó a la gente, lo que la mujer sagrada había ordenado. El jefe le dijo al eyapaha, el pregonero, y el pregonero recorrió el círculo del campamento llamando: “Alguien sagrado está llegando. Se acerca una mujer santa. Preparen todo para ella.” Así que la gente levantó la gran tienda de medicina y esperó. Después de cuatro días vieron a la Mujer Búfalo Blanco acercándose, llevando su paquete delante de ella. Su maravilloso vestido de piel de búfalo blanco brillaba desde lejos. El jefe, Cuerno Hueco Erguido, la invitó a entrar en la cabaña de medicina. Entró y rodeó el interior en el sentido del sol. El jefe se dirigió a ella respetuosamente, diciendo: “Hermana, nos alegra que hayas venido a instruirnos.”

Ella le dijo lo que quería hacer. En el centro de la tienda debían levantar un owanka wakan, un altar sagrado, hecho de tierra roja, con un cráneo de búfalo y un soporte de tres palos para una cosa sagrada que estaba trayendo. Hicieron lo que ella indicó, y ella trazó un diseño con su dedo en la tierra alisada del altar. Les mostró cómo hacer todo esto, luego rodeó la cabaña nuevamente en el sentido del sol. Deteniéndose frente al jefe, ahora abrió el paquete. Lo sagrado que contenía era el chanunpa, la pipa sagrada. Lo sostuvo frente a la gente y les permitió mirarlo. Sostenía el tallo con su mano derecha y la cazoleta con la izquierda, y así se ha sostenido la pipa desde entonces.

Nuevamente el jefe habló, diciendo: “Hermana, estamos contentos. No hemos tenido carne por algún tiempo. Todo lo que podemos ofrecerte es agua.” Sumergieron algo de wacanga, hierba dulce, en una bolsa de piel con agua y se la dieron, y hasta el día de hoy la gente sumerge hierba dulce o un ala de águila en agua y la rocía sobre una persona para purificarla.

La Mujer Búfalo Blanco mostró a la gente cómo usar la pipa. La llenó con chan-shasha, tabaco de corteza de sauce rojo. Caminó alrededor de la cabaña cuatro veces después del modo de Anpetu-Wi, el gran sol. Esto representaba el círculo sin fin, el aro sagrado, el camino de la vida. La mujer colocó un chip de búfalo seco en el fuego y encendió la pipa con él. Esto era peta-owihankeshni, el fuego sin fin, la llama que se pasa de generación en generación. Les dijo que el humo que se elevaba de la cazoleta era el aliento de Tunkashila, el aliento vivo del gran Misterio del Abuelo.

La Mujer Búfalo Blanco mostró a la gente la forma correcta de rezar, las palabras correctas y los gestos correctos. Les enseñó cómo cantar la canción de llenado de la pipa y cómo levantar la pipa hacia el cielo, hacia el Abuelo, y hacia abajo hacia la Abuela Tierra, hacia Unci, y luego hacia las cuatro direcciones del universo.

“Con esta pipa santa”, dijo, “caminarás como una oración viviente. Con tus pies descansando sobre la tierra y el tallo de la pipa alcanzando el cielo, tu cuerpo forma un puente viviente entre lo Sagrado Debajo y lo Sagrado Arriba. Wakan Tanka sonríe sobre nosotros, porque ahora somos uno: tierra, cielo, todas las cosas vivientes, los seres de dos patas, los de cuatro patas, los alados, los árboles, las hierbas.

"Mira este cuenco," dijo la Mujer Búfalo Blanco. "Su piedra representa al búfalo, pero también la carne y la sangre del hombre rojo. El búfalo representa el universo y las cuatro direcciones, porque se sostiene sobre cuatro patas, para las cuatro edades de la creación. El búfalo fue colocado en el oeste por Wakan Tanka al crear el mundo, para retener las aguas. Cada año pierde un pelo, y en cada una de las cuatro edades, pierde una pata. El círculo sagrado terminará cuando todo el pelo y las patas del gran búfalo se hayan ido, y el agua vuelva a cubrir la Tierra.

El tallo de madera de esta chanunpa representa todo lo que crece en la tierra. Doce plumas colgando de donde el tallo —la columna vertebral— se une al cuenco —el cráneo— son de Wanblee Galeshka, el águila moteada, el ave muy sagrada que es el mensajero del Gran Espíritu y el más sabio de todos los voladores. Estás unido a todas las cosas del universo, pues todas claman a Tunkashila. Mira el cuenco: grabadas en él hay siete círculos de varios tamaños. Representan las siete ceremonias sagradas que practicarás con esta pipa, y para el Ocheti Shakowin, las siete hogueras sagradas del consejo de nuestra nación Lakota".

La Mujer Búfalo Blanco luego habló a las mujeres, diciéndoles que era el trabajo de sus manos y el fruto de sus cuerpos lo que mantenía vivas a las personas. "Ustedes son de la madre tierra", les dijo. "Lo que están haciendo es tan grande como lo que hacen los guerreros".

Y por lo tanto, la pipa sagrada también es algo que une a hombres y mujeres en un círculo de amor. Es el único objeto sagrado en la fabricación del cual tanto hombres como mujeres tienen una mano. Los hombres tallan el cuenco y hacen el tallo; las mujeres lo decoran con bandas de púas de puercoespín de colores. Cuando un hombre toma una esposa, ambos sostienen la pipa al mismo tiempo, y un paño rojo de comercio se enrolla alrededor de sus manos, uniéndolos así por vida.

La Mujer Búfalo Blanco tenía muchas cosas para sus hermanas Lakota en su bolsa sagrada del vientre — maíz, wasna (pemmican), nabo silvestre. Les enseñó cómo hacer el fuego del hogar. Llenó un buche de búfalo con agua fría y dejó caer una piedra roja y caliente en él. "De esta manera cocinarán el maíz y la carne", les dijo.

La Mujer Búfalo Blanco también habló a los niños porque tienen una comprensión más allá de sus años. Les dijo que lo que sus padres y madres hacían era por ellos, que sus padres podían recordar haber sido pequeños una vez, y que ellos, los niños, crecerían para tener pequeños propios. Les dijo: "Ustedes son la generación venidera, por eso son los más importantes y preciosos. Algún día sostendrán esta pipa y fumarán con ella. Algún día rezarán con ella".

Habló una vez más a toda la gente: "La pipa está viva; es un ser rojo que les muestra una vida roja y un camino rojo. Y esta es la primera ceremonia para la cual usarán la pipa. La usarán para mantener el alma de una persona fallecida, porque a través de ella pueden hablar con Wakan Tanka, el Gran Espíritu Misterioso. El día en que muere un humano siempre es un día sagrado. El día en que el alma se libera al Gran Espíritu es otro. Cuatro mujeres se volverán sagradas en tal día. Ellas serán las que corten el árbol sagrado —el can-wakan— para el baile del sol".

Les dijo a los Lakota que eran los más puros entre las tribus, y por esa razón, Tunkashila les había otorgado la santa chanunpa. Habían sido elegidos para cuidarla por todos los pueblos indios de este continente tortuga.

Habló por última vez a Cuerno Hueco Erguido, el jefe, diciendo: "Recuerda: esta pipa es muy sagrada. Respétala, y te llevará hasta el final del camino. Las cuatro edades de la creación están en mí; soy las cuatro edades. Vendré a verte en cada ciclo generacional. Volveré a ti".

La mujer sagrada luego se despidió de la gente, diciendo: "Toksha ake wacinyanktin ktelo — Nos veremos de nuevo".

La gente la vio alejarse en la misma dirección de la que había venido, delineada contra el rojo sol poniente. Mientras se iba, se detuvo y rodó cuatro veces. La primera vez, se convirtió en un búfalo negro; la segunda en uno marrón; la tercera en uno rojo; y finalmente, la cuarta vez que rodó, se convirtió en una ternera búfalo blanca. Un búfalo blanco es lo más sagrado que se podría encontrar.

La Mujer Búfalo Blanco desapareció en el horizonte. Algún día podría volver. Tan pronto como se había desvanecido, aparecieron búfalos en grandes manadas, permitiendo ser sacrificados para que la gente pudiera sobrevivir. Y desde ese día, nuestros parientes, los búfalos, proporcionaron a la gente todo lo que necesitaban — carne para su comida, pieles para sus ropas y tipis, huesos para sus muchas herramientas.

—Contado por Lame Deer en Winner, Reserva India Rosebud, Dakota del Sur, 1967.

Se conservan dos pipas tribales muy antiguas por la familia Looking Horse en Eagle Butte, Dakota del Sur. Una de ellas, hecha del hueso de la pata de un ternero búfalo, demasiado frágil y quebradiza con la edad para ser usada para fumar, se dice que es la pipa sagrada que la Doncella Búfalo trajo al pueblo. "Lo sé", dijo Lame Deer. "Oré con ella una vez, hace mucho tiempo".

El continente tortuga es América del Norte, que muchas tribus indias consideran como una isla que se asienta sobre el lomo de una tortuga.

John Fire Lame Deer era un famoso "hombre santo" sioux, nieto del primer Jefe Lame Deer, un gran guerrero que luchó contra Custer y murió durante un enfrentamiento con el General Miles. El hijo de Lame Deer, Archie, continúa su trabajo como médico y director de danza de sol.